Zentrum für Internationale Lichtkunst Unna

Light Art Award 2017

Finalist Tilman Küntzel’s Fallen Chandelier

art-magazin June 2017

About his concept

I have been creating audiovisual installations ever since my time as a Fine Arts student at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg. I am interested in stimulating all the senses of people who experience my work, and I want them to be immersed in the work of art. By moving through the space people can determine their own perceptual process. I prefer to use dynamic algorithms from “found” control components, as in this installation for Unna, in which one experiences randomly generated movements of light and percussive sounds.

Why do you work with opposing concepts like crash and control or accident and intent?

The era of the Anthropocene is defined by control. Humankind aims to control nature, machines, and itself. Everything should be calculable. In contrast, a mistake or a malfunction is something subversive, something anarchical that escapes control and autonomously determines its owns processes. I am interested in how the dynamic of a malfunction develops in the sense of fostering aleatoric compositions and improvisation. A malfunction has its own aesthetic. Exploring and articulating this are important aspects of my practice.

Are the quiet and irregular switching sounds a significant part of your audiovisual installation?

The audiovisual installation for Unna is based on a sonification of a controlling system causing the flickering of forty light bulbs within a fallen chandelier. Twenty interconnected starters, similar those commonly found in fluorescent tubes, generate an irregular light rhythm. This occurs by means of bimetallic strips which are heated up in a tube and thus come in contact with one another in rapid sequence. This process is audible. Each starter generates its own rhythm, which has a different sound depending on the brand, make-up, and degree of wear of the starters. I first listen to a lot of starters before I use them for an installation (in the sense of “composing”). Your works are site-specific.

What makes the space at the Centre for International Light Art Unna a perfect spot for this artwork?

Its history. As John Jaspers once said, my work is about “storytelling.” The vaulted ceilings of the underground space remind me of an experience deep in the salt mines of Wieliczka, Poland (today a museum), where the miners had dug sixty- to eighty-meter long chapels and halls. One large space is decorated with an ornate chandelier made of salt crystals.

The vaulted underground space of the museum used to serve another purpose. This is a place where people worked, where things were produced and stored. With its lively play of lights and animated sounds, the fallen chandelier sparks visitors’ imaginations, encouraging people to develop their own stories about the place where the work unfolds.

Who or what has inspired you artistically, and/or has influenced your decision to work with light?

I am fascinated by natural constellations that exhibit any kind of special interplay between light and shadow. I am also inspired by the works of various artists such as Robert Wilson, James Turrell and John Cage. Cage in particular left a lasting impression on me with his choreography of light in „One11“, a film centred around the different effects of light in an empty room. Cage collaborated with multimedia artist Henning Lohner to make this film using only a single camera and spotlight projection. Regarding the film, Cage said: „No room is actually empty, and light will render – show – what there is in it.“ Cage also composed the piece „103“, which is played in parallel to the lights move – the speeds, arrangements and changes in the light, which become a musical composition in my mind.

What is your fascination to work with light as a material?

Influenced by the early 1980s, I love experimenting with the way our neurons respond automatically to the things we perceive – a concept embodied by the popular phrase „Turn on, tune in, drop out“. I like to incorporate this mode of perception into my work. As an audiophile, Iwas particularly shaped by sound as a additional mode of perception alongside vision, which is otherwise the most dominant mode of perception for most people. This is how I came to think of listening and seeing as two equivalent mode of perception. Those who study perception in the field of psychology say that what we see – a phenomenon that arises as a response to our need to give meaning to our sensory impressions. This kind of relationship between our perceptions of light and sound is what I primarily explore in my work.

What is your very first memory/encounter from childhood onwards of something you considered “art”?

I’m afraid my first foray into „art“ revolved around the music my family played at home, surrounded by contemporary art hanging on our walls. The music I was forced to play, however, was rather joyless, so it is not surprising that I developed a rebelliosus attitude as a result of this traumatic experience. I found my musical sanctuary in my friend Hansi, a canary bird – a type of bird that was typically found in many homes in the time shortly after the war. Listening to the canary’s enthusiastic singing in response to the noises at home – from the hoover, for example – was definately a formative experience for me and played an important role in my artistic and artistic and aesthetic development.

Wer oder was hat Sie als Künstler inspiriert oder Ihre Entscheidung beeinflusst, mit Licht zu arbeiten?

Mein erstes Objekt bestand aus einer Mandarinenkiste aus der eine Antenne herausragte. An dessen Ende war eine Plastikschüssel angebracht mit einem Telefonhörer-Lautsprecher darin. Im inneren der Kiste befand sich eine blau eingefärbte Fahrradbirne. Lautsprecher und Lämpchen waren an einen Walkman angeschlossen (linker Kanal: Lautsprecher, rechter Kanal: Lämpchen). Man hörte eine Familienfeier aus der Schüssel in der Antenne und sah das Flackern der blauen Birne, in gleicher Dynamik zum Klangereignis in der Kiste was einen eingeschalteten Fernseher assoziieren lies.

Als audiophiler Mensch dominiert bei mir die akustische Wahrnehmung neben der sonst üblichen Dominanz des Visuellen. So herrscht in meiner Wahrnehmung ein Äquivalent zwischen Hören und Sehen. In der Wahrnehmungspsychologie sagt man: „das Hören beschreibt das Sehen“ getrieben von der Notwenigkeit den Sinneseindrücken Sinnhaftigkeit zu verleihen. Als Kind der frühen 80er Jahre liebte ich es schon immer mit derartigen neuronalen Automatismen der Wahrnehmung zu spielen (Turn on, Tune in, Drop out!) und in der Kunst Teil der Rezeption des Kunstwerks werden zu lassen. So ist das Verhältnis von Licht zu Klang in der Wahrnehmung des Menschen zu meinem Hauptmedium in der Kunst geworden.

Was fasziniert Sie daran, mit Licht als Material zu arbeiten?

Ein schönes Bild stellt der Blick über eine Landschaft dar auf dessen Oberfläche einzelne Wölkchen am Himmel Schatten werfen die mit den Wölkchen über das Land hinweg ziehen. Es gibt diese Momente, in denen es in der Natur zu Konstellationen von Licht und Schatten, Stimmungen und Farben kommt, die wir erleben können wenn wir sie bemerken. John Cage hat vermocht diese Unverbindlichkeit des Bemerkens trotz konzipierten Konzepts zu bewaren; so auch mit der Lichtchoreographie „One11“. Ein Film über die Wirkung des Lichtes im leeren Raum, eine filmische Performance für eine Kamera und Scheinwerferprojektionen, entstanden 1992 kurz vor Cages Tod (in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Medienkünstler Henning Lohner). John Cage dazu: “….. kein Raum ist tatsächlich leer und das Licht wird zeigen, was darin ist.“ Cage hat diesem Film zwar die Komposition „103“ unterlegt, ich ziehe es jedoch vor diesen stumm zu sehen. Dabei begreife ich die Bewegungen, die Geschwindigkeiten, die Anordnungen und Dynamik als Komposition, die für mich im Kopf als Musik vorstellbar wird. Wie es auch beim Lesen von Partituren der Fall ist. Großartige für mich auch die Arbeiten von Robert Wilson und James Turrell.

Was ist Ihre früheste Kindheitserinnerung an etwas, das Sie als „Kunst“ betrachten?

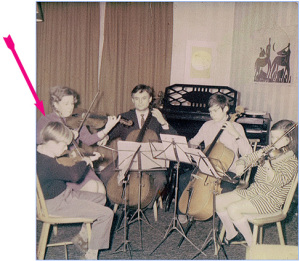

Ich fürchte dieses Bild von 1970 spricht für sich: Hausmusik im Kreise der Familie und zeitgenössische Kunst an den Wänden. An meiner Körperhaltung (vorne links) ist deutlich zu erkennen, dass diese Aktivitäten kein Spaß waren. Nicht verwunderlich, dass sich aus diesem Traumata eine rebellische Haltung entwickelte. Zuflucht fand ich in einem Kameraden, den viele Nachkriegshaushalte beherbergten. Den Kanarienvogel namens Hansi. Sein enthusiastischer Gesang in Respons auf den Lärm eines Staubsaugers war sicher für meine künstlerisch-ästhetische Entwicklung ein prägendes Erlebnis.